Here be dragons, and tigers

Monday | October 6, 2014 open printable version

open printable version

Revivre.

DB here:

My first visit to the Vancouver International Film Festival back in 2005 was at the invitation of Tony Rayns, programmer of the Dragons and Tigers series. That series included both new films by established directors and a batch of first or second features by beginners. Tony asked me to be on the jury for the young D & T award.

I enjoyed working on that jury, which consisted of old friend Li Cheuk-to of the Hong Kong Film Festival and new friend Gerwin Tamsma of the Rotterdam fest. We gave the prize to Liu Jialin’s Oxhide, and it’s been gratifying to track her career since. In the course of my stay I realized what an excellent festival Vancouver had, not least because of the warmth and enthusiasm of its staff.

My Vancouver experience helped launch this blog, which really got under way during my second visit, in several entries in 2006. That was also the year I met Bong Joon-ho, who was at VIFF with The Host. I kept going back, and Kristin began joining me, so every year we’ve been writing about this admirable event.

During that 2006 festival Tony decided to rearrange his commitment to Dragons and Tigers. He turned the curating of Chinese-language films over to expert programmer Shelly Kraicer, who was living on the mainland and had excellent contacts within China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. Now things have changed again. This year the festival accepted fewer beginners’ features and folded them into a broader international competition. One of the Asian films in the collection, Rekorder by Mikhail Red, tied with a French entry, Miss and the Doctors, for the award. In the old days, the winner received a cash prize; alas, that benefit has not been retained, but maybe some far-sighted patron will step forward to give the award a little more heft.

There were fewer D & T titles overall this year, but I still found several of great interest. Herewith some notes on them.

Time, and time again

Revivre.

If your movie is going to include flashbacks, you have a choice among several standard ways of motivating them. You can use the very old device of presenting an investigation or trial, in which the film translates testimony into dramatized scenes. Or you might frame the flashbacks with a scene of a character who thinks back on events in the past. Three of the Dragons and Tigers films used some other common flashback setups, but treated them in fresh ways.

Im Kwon-taek’s Revivre (Hwajang, his 102nd film!) starts with another canonical flashback situation. In fairly washed-out footage a funeral procession crosses the screen. A man at the head of the group looks back and sees a beautiful young woman looking gravely at him. Immediately the film triggers questions: Whose funeral is this? Why is the young woman important?

The rest of the film fills us in via flashbacks,. The protagonist, Oh Sang-moo, is a manager of the advertising section of a cosmetics company. His wife is stricken with a brain tumor and he cares for her as best he can during her years of surgery and recovery. At the same time, he develops a restrained affection for Ms. Choo, an employee in his division. Eventually Oh’s wife dies and there is the lingering possibility of his starting his life afresh with Ms. Choo, whose phantom face we’ve seen in the procession. Threaded through this are the pressures of a business deadline, his need to keep his staff on track, his occasionally fraught relations with his daughter, and his wife’s adamant insistence that after she dies he keep none of her things, not even her beloved dog.

The film scrambles the order of Oh’s experiences. After the funeral, within about five minutes we get a scene of Oh’s wife dying in the hospital, then a scene of his own medical problems, and then the moment that Oh’s wife collapsed in the garden, yielding the first sign of a tumor. The rest of the film gives us incidents from all phases of their last years together, with emphasis on his careful attention to her bodily functions. Although his daughter finds the task repellent, Oh changes his wife’s diapers and cleans her private parts with the same calm professionalism that he brings to the meetings in his company. In all, the non-chronological flashbacks work effectively to show Oh juggling the pressures of business with the demands of his family situation.

What makes Im’s treatment a little unusual is that the flashbacks aren’t presented as Oh’s memories. They are rearranged by the narrational authority of the film itself, rather than by situations that provoke Oh to recall this or that incident. We’re restricted to Oh’s range of knowledge throughout, but that doesn’t draw us closer to him. We have to read his mind through his expressions and his gestures, and these are often severely controlled. A master of the poker face, this executive keeps a polite distance from everyone, including the viewer. Is he one of nature’s stoics? Or is he emotionally detached, attending to his dying wife more out of duty than love?

These questions are partly answered by some brief fantasy scenes in which Oh visualizes Ms. Choo as a romantic partner. She seems to intuit his interest, and responds through small signals. When she starts to reciprocate more explicitly, Revivre returns to its mood of impassive sadness for its final scenes.

Time and freedom

Hong Sangsoo has been playing with time from the start of his career. He has tried replays from different viewpoints (The Power of Kangwon Province, 1998), replays that differ in details (The Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, 2000), odd déjà-vu experiences (Turning Gate, 2002), and all manner of theme-and-variations plotting (as noted on this blog here and here and here). So it’s a bit surprising to find him exhuming the old reliable setup of letters recounting events in the past. Yet here as ever he has a couple of tricks up his sleeve.

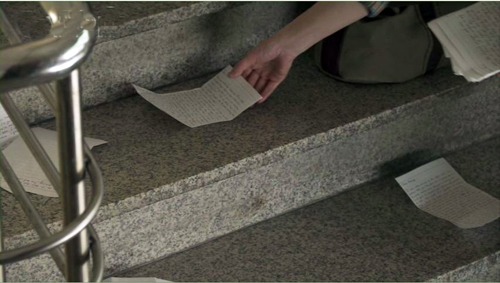

Like Im, Hong has scrambled the flashbacks in Hill of Freedom, but he offers a comically exact motivation. Kwon, a young language teacher in Seoul, returns to find a sheaf of letters written to her by a Japanese admirer, Mori. He taught with her at the school two years earlier. He has come to Seoul to reunite with her, and he has left her a letter every day. She starts to read them in the school lobby, and Mori’s voice-over narration establishes the beginning of his story. He tells how he found lodging, left a note at Kwon’s apartment, and paid his first visit to the “Hill of Freedom” café.

So far, 1-2-3 preparation. But when Kwon starts to leave the language institute, she staggers on the staircase, as if stricken, and scatters the letters on the steps. She gathers them back up in random order. This sets up the scrambled timeline of the flashbacks to come. (Hong mischievously zooms in on a letter she fails to retrieve, hinting at a gap in the story that will follow.)

What Kwon learns, in mixed-up order, is that Mori’s search for her leads him to meet and hang out with his landlady’s nephew, while also becoming romantically involved with Youngsun, the café owner. In the grip of a possessive lover, Youngsun attaches herself to the fairly passive Mori. Their affair plays out in Hong’s usual mix of drinking bouts and pillow talk.

By the time we’re used to this pattern, Hong sets up a new game. As he keeps cutting back to Kwon reading through the letters, accompanied by Mori’s voice-over, Hong gradually reveals that she is reading them in the Hill of Freedom café—the very place Mori hoped to meet with her (but never did).

Eventually, Kwon steps outside for a cigarette, and we suddenly get her voice-over remarking that the last letter was postmarked a week ago. Has Mori then already left and stopped writing? At this point Kwon encounters Youngsun coming in, and they greet each other as friendly acquaintances. The next scene finds Kwon visiting Mori’s guest house.

What happens there shifts the ground under our feet. After talking with friends, I think that we can’t be sure about what’s actually taking place. A mysteriously bruised cheek, a surprise reunion, and the return of Mori’s voice-over fill the penultimate scene. The coda is even more of a puzzler, at least to me. (I wonder if it’s the scene described in the letter that Kwon didn’t retrieve.) In any event, Hong’s usual themes of the foolish arrogance of Korean men and the comedy of male-female interactions are given new expression in this lightweight but enjoyable movie. The fact that Hill of Freedom is mostly in English, which Mori must employ to communicate with the Korean characters, adds to the fun.

Video virus

Yet another trigger for a flashback can be provided by a crisis situation. It might be rather near the story’s climax, so that we are left hanging and the plot takes us back to the origins of the problem. This is what we get in movies like The Big Clock (1947), which starts with our hero hiding out from the police and wondering how he got in this pickle. Or the crisis situation may come earlier in the story, with the flashback again filling in what led up to it before continuing the situation presented in the frame.

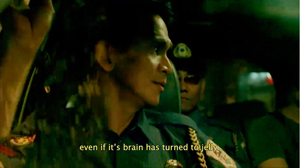

This latter option is followed in Mikhail Red’s Rekorder. After a brief prologue showing violent acts captured by CCTV cameras, we are in a police van with stern cops chatting about killing a dog before we’re introduced to the shaggy, wasted protagonist Maven riding with them.

From this framing situation we flash back to the reason Maven is in the van. Once a cinematographer in the glory days of Filipino cinema, he’s now a loner using his ancient camcorder to film movies in theatres and sell them to a friend who bootlegs DVDs.

Maven is a compulsive recorder. As the director puts it, he is “a ghost in the city observing everything through his lens.” So naturally he’s filming when a street gang kills a young man in front of a crowd who simply watch. Maven doesn’t volunteer his footage, since it includes part of a movie he was pirating. But now he’s been nabbed and is riding to headquarters with the cops, who are very curious about what’s on his tape.

Much of the rest of the film involves Maven’s attempt to keep the cops from examining his footage, while he agonizes about his passive acceptance of street violence. There are still more flashbacks, appropriately presented through old video footage of his wife and daughter. Not until the end of the film do we witness–again, on CCTV footage–the trauma that has turned him into the burnt-out case he is.

Mikhail Red commented that he was inspired to make Rekorder by a viral video in which a youth was shot in the street by thugs and a big crowd didn’t intervene but instead filmed the murder. He staged his own CCTV-style video to supply the denouement, and was shocked to find that it was appropriated in documentaries about street crime. Through a multimedia format, Rekorder updates the sort of social criticism that Raymond Red, Mikhail’s father, brought to Filipino cinema of the 1980s. That era as well is evoked through another sort of flashback, the clips from classic movies that Maven films. “I wanted,” Red says, “to pay homage to the pioneers.”

Straight time

You don’t need to play time tricks to create an uneasy movie. Ow (Maru) presents a typical family squeezed by Japan’s economic stagnation. Dad pretends to have a job, when he actually sets out each day for the unemployment office. Mom and grandma putter about. Grown but spacy Tetsuo lounges about his room talking baby talk. One day, when his girlfriend has just snuggled into bed with him, they are transfixed by a big gray-brown sphere that drifts into his room.

Transfixed, literally. They freeze upon seeing it. So does Dad, and so do the cops who are called. Director Suzuki Yohei introduces us to the big ball with a shot of it slowly spinning, held long enough for us to get slightly hypnotized too. There follows some comic suspense in which people enter the bedroom and may or may not leave. The biggest tease is the reporter who, after learning of a death during the sphere’s arrival, researches the case and then lunges into the room, ranting about a police cover-up.

The tension–will others fall under the spell or the sphere?–is accentuated by shrewd camera setups. When the cops arrive, we get a low-angle shot behind Yuriko and Tetso, showing the frozen cops and a new one not yet transfixed. He pushes one stiff colleague over, revealing the ball, still hovering there, and we wait for him to be the new victim.

Much later, when the reporter first visits the room, the sphere has vanished. But a rhyming angle forces us to remember its presence, and to let the reporter–the source of the plot’s momentum for the rest of the movie–take the place of the hapless cop.

Finally, for another exercise in unkinked time, there is the Korean action picture Haemoo. Produced by Bong Joonho, it centers on the desperate captain of a fish-trawler who agrees to bring illegal immigrants into Korea. Everything that could go wrong does: storm, fog, Coast Guard patrols, a horny crew, and an idealistic novice seaman who tries to protect a woman. Everything, including the accident that creates a horrifying midway turning-point, is carefully prepared in the film’s opening scenes. The film’s second half locks us into the relentless consequences of covering up a huge crime.

The pace is so snappy that I expected lots of cutting, but I counted only about eight hundred shots in 106 minutes. (The Equalizer, only twenty minutes longer, has three times that number.) I attribute this cutting rate to neatly functional direction, with no fuss or waste. The ship’s engine room is a cramped set, hazy with steam and dust, and the shots there are finely calibrated to build the drama through depth, fluid camera movement, and our old friend The Cross. The randy engineer’s business of checking the equipment carries him from one side of the shot to the other, while the young seaman shifts around him–first on frame right, then on frame left, then in the center.

The plot has that satisfying neatness that is characteristic of Bong’s work, and its forward thrust has no need of flashbacks. We can’t ask for backstory when the upcoming twists are as fast-paced and exciting as they are here. Dragons and Tigers has always showcased not only the experimental films like Ow and Hill of Freedom but also the crowd-pleasers, and Haemoo (which translates as “Sea Fog”) solidly fulfills that mission. Long live linearity!

Hill of Freedom has sharply divided critical opinion. Richard Brody considers it a masterpiece; others consider it fluff. At Fandor David Hudson painstakingly surveys the cut and thrust of the controversy.

Hill of Freedom.